Saturday, 15 October 2011

Saturday, 8 October 2011

Auschwitz-Birkenau

When I was a teenager I became friendly with an aging Polish woman called Sophie Sydow. She mentored me through my musical listening and we spent hours, at the record shop she managed, her getting me to try recordings, explore music, gain some kind of critical standards and telling me a great deal about life in Poland before and during WWII.

It was a pretty tragic tale. Her father had been a diplomat. He simply disappeared. A week later her sister was raped and murdered and her brother hung himself in the nearby woods, Sophie found the body. Other relatives were bundled off into concentration camps. She met up with her husband Matt and supported him in the Polish Resistance. Later they came to the UK to escape communism and lived a quiet life looking after stray animals, on a fairly epic scale.

But even in the 1970s life provided new tragedy. Her only child, Nina, was murdered in Greece. Assaulted and left face down in a puddle the girl drowned. Sophie spent much money and ended up losing her job while she travelled back and forth to challenge the lack of outcome from the investigations of the Greek authorities. She died of heart disease, a heart-sick woman in many ways. Matt lived on for about 15 years looking after the animals.

Her story pervaded my impressions of Poland, once a wonderful country, hugely depleted by the nazi invasion, then communist suppression.

I thought about her when we were in Krakow, though her family was from Warsaw. I thought about her when we visited Auschwitz-Birkenau.

What are visitors up to when they come here? The Second World War finished 66 years ago. The oldest people I saw there would have been children then, but could well have gone to remember relatives of an earlier generation. One or two quite young Jewish men were clearly distressed. Some people came to make commemoration.

But how about all of us who are tourists? Those of us who have no known connection to the people who perished there. We variously went to the salt mines, we climbed up to the castle at Krakow, we took a bus trip to the concentration camp.

Before we went I was very ambivalent about this trip. My wife was intent upon it and fine about going alone. I had been told it was tidy, clean and there were nice trees all around. Of course, it had to be sanitised for so many reasons, but I did not like the hint of theme park that was suggested by more than one person.

We did both however go. Facilely I wondered what the weather would be like. Surely, it at least ought to be raining. Sunshine would be inappropriate; despite it being obvious that there would have been normal weather in the area when it was full of prisoners. Somehow, I imagine it to exist in a black and white world of wartime film.

It was sunny. Despite this, there was plenty to make one go cold if not actually numb. We thought that we had a reasonable grip on what had happened and why; no, our knowledge was half digested, barely half remembered.

The journey out from Krakow takes about an hour and a half. On the bus there were about 25 people, one retired couple, us and then the next oldest would be about 30. Three young twenties females sat near us and were intent on phone swapping last night's drinking photos. But the organisers had other ideas and a documentary film was put onto the system. The group fell silent.

These two camps were liberated by the Russians. The film was shot by a cameraman who, 40 years later, explained the circumstances; one of which was that at the liberation the inmates were frightened and traumatised. There was no joy and there were no smiling faces. In an attempt to provide more appropriate propaganda; months later some former prisoners were coaxed to return and seemingly burst out of their prison as the Russians arrived; joy unconfined and these remnants strode cheerily in front of the camera, waving, smiling and well dressed.

Some kind of sense prevailed and the reconstructions were never used. The film was silent about the Russians basically moving a number of prisoners to Russian work-camps. Silence also prevailed on the bus from the start of the film until we arrived at Auschwitz. A kind of preparation for the visit had taken place.

The names of the camps were Germanised versions of the local Polish place names. Auschwitz was the first camp. As such, its design was not up to the Final Solution in its comparitave lack of factory efficiency. The gas chamber could only accommodate around 250 killings at a time and darn it, the warehouses storing the possessions of the victims was an inconvienient distance from the railway. Auschwitz had been set up primarily as a labour camp. So, once the trawling in of the Jews, Gypsies, Political Prisoners, Homosexuals and general undesirables became a Europe Wide policy for the nazis, the nearby Birkenau was set up on a staggering scale as part slave camp, part killing ground.

By January of 1945 it became clear that the Germans would lose the war and in preparation for withdrawal there was a half hearted attempt to dispose of evidence by blowing up the underground gas chambers in Birkenau and march off the prisoners who were deemed possibly useful. On the vast site only around 5,000 survivors remained to be rescued.

Birkenau was a kind of model camp and over 30 others were built in Upper Silesia.

Even young and strong looking people, if they arrived in January, they would almost all be dead by March. The sole clothing; thin striped suits and clogs, was no defense against the cold. Brutality was a default setting. Minor infringements were met with various tortures or deprivations, including the 'four to a cell'. The cell being about the size of a telephone box; many suffocated from this treatment.

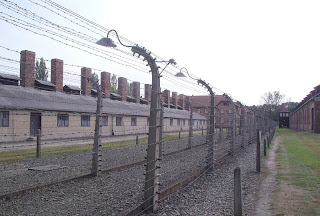

Many committed suicide by holding onto the electric wire fencing.

Those with the first 1000 numbers tattooed onto them often lasted the full five years. These initial inmates were the inside admin workers and escaped the worst privations of working outside each winter. First in and last out in a strange twist of fate.

Birkenau

It was a pretty tragic tale. Her father had been a diplomat. He simply disappeared. A week later her sister was raped and murdered and her brother hung himself in the nearby woods, Sophie found the body. Other relatives were bundled off into concentration camps. She met up with her husband Matt and supported him in the Polish Resistance. Later they came to the UK to escape communism and lived a quiet life looking after stray animals, on a fairly epic scale.

But even in the 1970s life provided new tragedy. Her only child, Nina, was murdered in Greece. Assaulted and left face down in a puddle the girl drowned. Sophie spent much money and ended up losing her job while she travelled back and forth to challenge the lack of outcome from the investigations of the Greek authorities. She died of heart disease, a heart-sick woman in many ways. Matt lived on for about 15 years looking after the animals.

Her story pervaded my impressions of Poland, once a wonderful country, hugely depleted by the nazi invasion, then communist suppression.

I thought about her when we were in Krakow, though her family was from Warsaw. I thought about her when we visited Auschwitz-Birkenau.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

What are visitors up to when they come here? The Second World War finished 66 years ago. The oldest people I saw there would have been children then, but could well have gone to remember relatives of an earlier generation. One or two quite young Jewish men were clearly distressed. Some people came to make commemoration.

But how about all of us who are tourists? Those of us who have no known connection to the people who perished there. We variously went to the salt mines, we climbed up to the castle at Krakow, we took a bus trip to the concentration camp.

Before we went I was very ambivalent about this trip. My wife was intent upon it and fine about going alone. I had been told it was tidy, clean and there were nice trees all around. Of course, it had to be sanitised for so many reasons, but I did not like the hint of theme park that was suggested by more than one person.

We did both however go. Facilely I wondered what the weather would be like. Surely, it at least ought to be raining. Sunshine would be inappropriate; despite it being obvious that there would have been normal weather in the area when it was full of prisoners. Somehow, I imagine it to exist in a black and white world of wartime film.

It was sunny. Despite this, there was plenty to make one go cold if not actually numb. We thought that we had a reasonable grip on what had happened and why; no, our knowledge was half digested, barely half remembered.

The journey out from Krakow takes about an hour and a half. On the bus there were about 25 people, one retired couple, us and then the next oldest would be about 30. Three young twenties females sat near us and were intent on phone swapping last night's drinking photos. But the organisers had other ideas and a documentary film was put onto the system. The group fell silent.

These two camps were liberated by the Russians. The film was shot by a cameraman who, 40 years later, explained the circumstances; one of which was that at the liberation the inmates were frightened and traumatised. There was no joy and there were no smiling faces. In an attempt to provide more appropriate propaganda; months later some former prisoners were coaxed to return and seemingly burst out of their prison as the Russians arrived; joy unconfined and these remnants strode cheerily in front of the camera, waving, smiling and well dressed.

Some kind of sense prevailed and the reconstructions were never used. The film was silent about the Russians basically moving a number of prisoners to Russian work-camps. Silence also prevailed on the bus from the start of the film until we arrived at Auschwitz. A kind of preparation for the visit had taken place.

The names of the camps were Germanised versions of the local Polish place names. Auschwitz was the first camp. As such, its design was not up to the Final Solution in its comparitave lack of factory efficiency. The gas chamber could only accommodate around 250 killings at a time and darn it, the warehouses storing the possessions of the victims was an inconvienient distance from the railway. Auschwitz had been set up primarily as a labour camp. So, once the trawling in of the Jews, Gypsies, Political Prisoners, Homosexuals and general undesirables became a Europe Wide policy for the nazis, the nearby Birkenau was set up on a staggering scale as part slave camp, part killing ground.

By January of 1945 it became clear that the Germans would lose the war and in preparation for withdrawal there was a half hearted attempt to dispose of evidence by blowing up the underground gas chambers in Birkenau and march off the prisoners who were deemed possibly useful. On the vast site only around 5,000 survivors remained to be rescued.

Birkenau was a kind of model camp and over 30 others were built in Upper Silesia.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

We encountered our guide at the entry to Auschwitz. We were given headphones and a receiver. The guide confided the facts and figures as though just to each individual, like a voice inside your head. Even when in another room, she spoke directly into my ear. She was short, red haired, in her late 40s and with a deep gravel voice. Her delivery was succinct, low key, but exceptionally powerful. Throughout the entire three hours, the words 'German' and 'Germany' never passed the lips of the guide. Auschwitz had been staffed only by SS and reference made to nazis. German visitors are allowed the dignity of being distanced from the perpetrators. Rather more dignity than was allowed to the more than 1,000,000 people who died within the two camps.

Currently I am re-reading Upton Sinclair's 'The Jungle'. It tells the story of the Chicago stockyards at the turn from the 19th Century to 20th. Eastern European immigrants were exploited there and the ever innovative factory owners boasted of a system utilising every part of a pig except its squeak. Bones became fertiliser or buttons or combs, hides made into all sorts; the meat itself vital, but by no means the sole product. The meat-packer owners set up adjacent soap and glue factories. The area became ultra efficient at making money for the rich; and notorious for the way the health of the workers was carelessly damaged. Like Dickens before him, Sinclair exposed to the world unethical methods of production and the outrage effected some changes of law to lighten the lives of those blighted by the system.

All of that factory efficiency and ingenuity in the use for any part of the animal came to mind during the tour of the prison camps. The first thing to go was your dignity. 70 people in a rail truck with only a bucket as a toilet and transported up to 2000 kms from as far as Greece or Norway. Lack of privacy across perhaps 10 days, lack of food or water; living amongst those who died all added to the great heat or extreme cold to produce an initial filter for those too old, young or weak to survive the conditions of the journey.

At journey end those stumbling out of the trucks were lined up and men were separated from women. Their 25 kilos per head of luggage was left on the platform to be stored in warehouses once the contents were sorted. Those deemed strong were marched off to the work camp, the others 'cleaned' up, hair chopped off, clothes removed and then driven into the gas chamber, then dragged to the ovens.

The nazi's were big on admin, so notated in detail the millions of dresses, coats, shoes, suits, pairs of glasses and artificial limbs confiscated to be sold to the citizens back in Germany. Hair was all treated to make clean it and bailed like hay. It was then woven into fabric, socks for submariners, blankets. Gold was pulled out of the teeth of the dead. After a while, the water sources now grey and clogged with human ashes, they spread new ashes across the nearby fields as fertiliser. After the war the collected hair was chemically tested as it was uniformly grey, it bore traces of Zyklone B, despite it having been removed prior to death. The air outside the chambers must have been invaded by small penetrations of it.

Gypsies, twins and any other people deemed of interest were experimented on in the hospital; Mengale who lead the work escaped a few days before the Russians arrived; he was never caught.

So, what were the ones who were chosen to work actually doing?

Once the much larger Birkenau was being built, many German factories were re-sited out of Germany into the area and contracts were set up between the industrialists and the camps for a continuous fresh supply of slave labour. Too many were dying merely of the long walks to the factories, thus mini camps sprung up around the furthest away ones.

IG Farben was one of the largest industrial companies in the world. It chose which factories it wanted to take over and to extend using slave labour on the building works and as workers in its chemical factories. It produced much of the Zyklon B that was used to kill its own slave labour. To date shares in the company continue to be traded; though it is in a continued state of liquidation with assets worth many millions of Euros.

A subsistence diet was provided. The accommodation was in crowded huts with poor heating and gaps between the top of the walls and the roof. The winter temperatures were similar out or in the huts. Going round and gazing at corridors of photographs of the inmates, each had three pieces of information, birth date, date of admission, date of death.

Once the much larger Birkenau was being built, many German factories were re-sited out of Germany into the area and contracts were set up between the industrialists and the camps for a continuous fresh supply of slave labour. Too many were dying merely of the long walks to the factories, thus mini camps sprung up around the furthest away ones.

IG Farben was one of the largest industrial companies in the world. It chose which factories it wanted to take over and to extend using slave labour on the building works and as workers in its chemical factories. It produced much of the Zyklon B that was used to kill its own slave labour. To date shares in the company continue to be traded; though it is in a continued state of liquidation with assets worth many millions of Euros.

A subsistence diet was provided. The accommodation was in crowded huts with poor heating and gaps between the top of the walls and the roof. The winter temperatures were similar out or in the huts. Going round and gazing at corridors of photographs of the inmates, each had three pieces of information, birth date, date of admission, date of death.

Even young and strong looking people, if they arrived in January, they would almost all be dead by March. The sole clothing; thin striped suits and clogs, was no defense against the cold. Brutality was a default setting. Minor infringements were met with various tortures or deprivations, including the 'four to a cell'. The cell being about the size of a telephone box; many suffocated from this treatment.

Many committed suicide by holding onto the electric wire fencing.

Those with the first 1000 numbers tattooed onto them often lasted the full five years. These initial inmates were the inside admin workers and escaped the worst privations of working outside each winter. First in and last out in a strange twist of fate.

The 'wall of death' in Auschwitz was where prisoners were shot, no one can even guess how many. Mobile gallows were trundled about and if any prisoner escaped, 10 were randomly chosen during roll call and hung in front of the assembly.

Over at Birkenau the railway tracks run the 1200 meters through the centre of the camp, dividing it; women's camp to one side of the track, mens' on the other. Half way along a wooden rail cattle-truck is sited to mark 'The Place of Choosing'. Here, as the people were disgorged, immediate decisions were taken by doctors. The doctor indicated with his thumb to left or to right, each was then consigned either to the gas chamber or to the work huts. Those to die were walked 600 meters to the new underground chambers to be gassed. 5000 could be disposed of a day, despite which, evidence emerged that the ovens could not cope and bodies were also burned in the ground around the gas chambers.

No one of us asked a single question. People were silent, absorbing, learning and of course, taking lots of photos. The ride back on the bus was quiet, not silent, but subdued. What got to me most was not the cells, not the gallows or the 'Wall of Death'. It was the tons of hair, thousands of spectacles. If you could not see, too bad, you were a kind of fodder now, not a person. Everything removed, people exploited to the uttermost, their very dust utilised by the Third Reich; deploying feelingless conveyor-belt methods. Treated like animals in the Chicago stockyards. Like animals.

What did I take away. At 58 is it yet possible to be disappointed and dispirited at the way we deal with one another? Yes.

Auschwitz:

What did I take away. At 58 is it yet possible to be disappointed and dispirited at the way we deal with one another? Yes.

Auschwitz:

'Freedom Through Work'

Hair

Birkenau

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)